Strawberry Ferry

Initially, the ferry served to transport livestock, enslaved people, carriages, and other passengers across the Cooper River to and from the short-lived town of Childsbury, which surrounded Strawberry Chapel.

The Strawberry Ferry served as a vital mode of transportation across the Cooper River for 225 years.

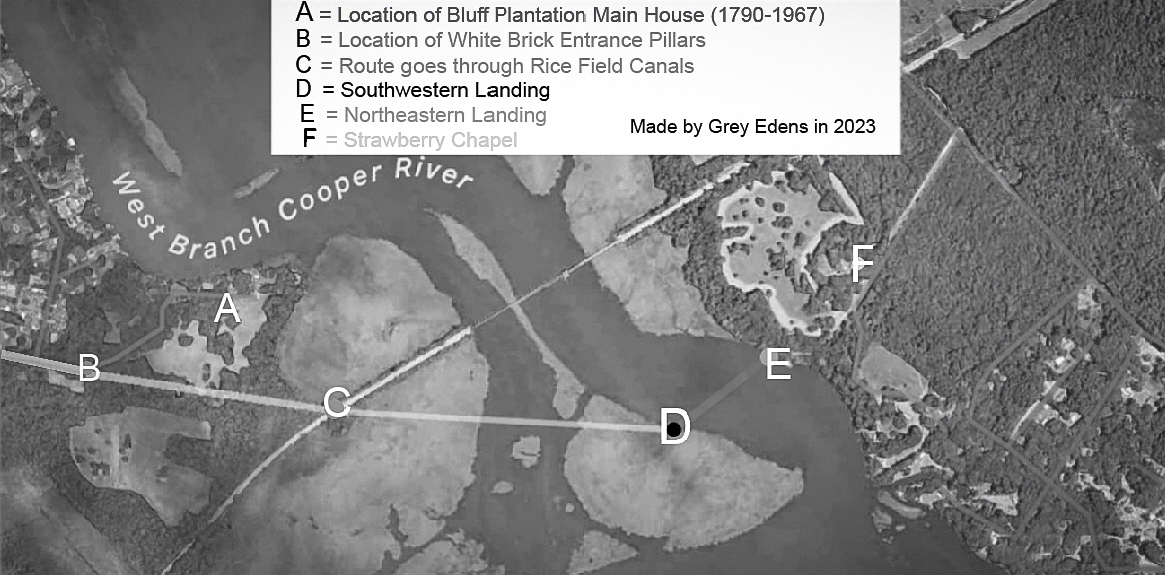

The Strawberry Ferry was established by an act of Assembly on February 17th, 1705. The ferry was located near the “T” where the eastern and western branches of the Cooper River meet. White brick pillars, which still stand today, mark the entrance of Strawberry Ferry Road at the Bluff Plantation on the west side of the ferry. The ferry’s landings were situated on the rice banks of the Bluff Plantation and the east riverbank adjacent to Strawberry Chapel. However, the main landing was on the east riverbank, where the enslaved people that operated the ferry lived. The landings were 2 ½ meters wide and had a patterned brick floor supported by logs.

Initially, the ferry served to transport livestock, enslaved people, carriages, and other passengers across the Cooper River to and from the short-lived town of Childsbury, which surrounded Strawberry Chapel. In 1748, the ferry cost two pence for cattle, three pence per passenger and horse, and one shilling per chaise or wagon. The town of Childsbury was started by Englishman James Child and had a school, race track, general store, and chapel. Additionally, there was an inn and tavern that served ferry travelers and town residents. Following the town’s demise around 1740, it was absorbed into the nearby Strawberry plantation. The ferry’s main function became transporting passengers to Strawberry Chapel for church services or to neighboring plantations.

During the Revolutionary War the Bluff Plantation was owned by Major Isaac Child Harleston, who served on the staff of General Francis Marion. Across the ferry, Strawberry Plantation was the property of young tory Elias Ball III. On July 15, 1780, on the east side of ferry, British forces came ashore from their frigates and marched to a chapel, Biggin Church, a few miles north. As the troops disappeared up the path, a rebel detachment fell on the contingent left behind, took fifty prisoners, and burned four of the ships anchored in the river.

Mary Louisa Moultrie Ball, who grew up on the Bluff Plantation, recounts the ferry as it operated around 1850; “…Daddy Casey and “Abr’am” were the two negroes who carried the flats back and forth and lived in two little houses side by side on The Ferry side of the river. One wanting to cross would have to whoop for them if he were on The Bluff side, and one of them would come out and laboriously row his craft across to receive and transport whoever it was. Several times when it was dark and cold these negroes, who dearly loved a fire, would pretend not to hear the call, whereupon one of the gentlemen would fire a load of buckshot in the direction of their houses to let them understand that there was someone there to whom it was imperative to cross,—and this method of communication never failed to bring results… On Sundays The Ferry flats would wait for a load before leaving, and as the different families would gather, their vehicles would dump them and turn and drive to The Bluff, there to wait until they saw the flats start from the other shore after service at Strawberry Chapel, when they would again hitch up and drive down to the slip to receive them…”

In 1930, after 225 years of operation, the Ferry ended due to the construction of the Atlantic Coast Railway, which blocked the path of Strawberry Ferry Road.

Sources:

“Strawberry Chapel and Childsbury Town Site”, South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

“Country chapel built in 1725 is all that remains of Colonial-era town near Charleston,” The Post and Courier.

“Strawberry Ferry and Childsbury Towne: A Socio-Economic Enterprise on the Western Branch of the Cooper River, St. John’s Parish, Berkeley County, South Carolina,” William B. Barr, The South Carolina Institute of Archeology and Anthropology–University of South Carolina.

“Bluff Plantation Wildlife Sanctuary History,” South Carolina Historical Society.

“A teacher’s field guide to the natural history of the Bluff Plantation wildlife sanctuary,” Richard D. Porcher.

“Slaves in the Family,” Edward Ball.

“A Day on the Cooper River,” John Beaufain Irving.